What is Knowledge Work

Definition and examples

Abstract

The significance of knowledge, skills, and experience in any job cannot be overstated. Whether it's a surgeon performing a complex operation, a software developer writing code, or an assembly line worker building products, each role requires a certain amount of knowledge to achieve success. This article explores the concept of knowledge work, defining its terms, and examining its necessity and implications in modern professions.

Knowledge work involves the cognitive effort to close the gap between what is known and what needs to be known in order to effectively complete a task. It becomes necessary when there is an imbalance between required knowledge and prior knowledge. Understanding this concept is crucial as different professions demand varying proportions of manual and knowledge work.

While some jobs embed much of the required knowledge within the tools and procedures used, others necessitate continuous learning and adaptation to bridge the gap between existing skills and the demands of the task. This variability highlights how the same profession, when executed by people with different levels of prior knowledge, can require different proportions of knowledge work.

Adopting a knowledge-centric perspective focuses on discovering missing knowledge while still managing the manual aspects of work. This approach provides a holistic view when combining knowledge-centric and manual-centric perspectives on all human activities. By understanding the balance between cognitive and manual efforts in various jobs, we can appreciate the diverse skill sets required across different fields and recognize the continuous learning and adaptation involved in all forms of work.

Context and Perception

Currently, the term "knowledge work" often encompasses jobs predominantly associated with manipulating, analyzing, and creating information, such as software development. It is often juxtaposed to manual labor and skilled trades, such as carpentry.

Despite its prevalence and relevance, "knowledge work" has faced criticism and skepticism. Many argue that it implies a hierarchy where knowledge work is viewed as inherently superior to manual labor. This perception can undervalue the intellectual engagement and expertise required in many skilled trades and professions that are not traditionally viewed as knowledge work, such as pilots, surgeons, and teachers. In my opinion, the reason people think carpentry is less of a knowledge work than software development is because the former requires learning a smaller body of knowledge than the latter. That is, people look from a static perspective on prior knowledge.

The Fundamentals of Any Job

Let’s take a first principles approach to what work is. Every task comprises two major types of labor - cognitive and manual. The manual labor involves muscle effort and results in a tangible output. The cognitive labor involves answering the fundamental questions of "what," "how," and "why" to complete a task[2]:

- What needs to be done?

- How should it be done?

- Why is it being done?

Each of these questions can be broken down into more detailed questions in a fractal manner to infinitely small questions. Eventually, when these questions are answered, the person can proceed with manual labor. Importantly, the muscles are commanded by the brain, thus the cognitive labor always precedes the manual labor for a task.

Knowledge to Be Discovered

For each of the questions, there is a required level of knowledge and prior level of knowledge. The Required Knowledge is the complexity of the task at hand i.e., what needs to be known. Prior Knowledge is the existing skills and knowledge an individual possesses i.e., what is known. The gap between required and prior knowledge is the Knowledge to Be Discovered.

From that, we present our definition of knowledge work:

Imagine a scale: on one side is the required knowledge and on the other is the prior knowledge. They will be balanced if they are equal, implying that the knowledge to be discovered equals zero. A balanced scale implies no need for additional knowledge; an imbalanced scale necessitates knowledge acquisition.

Peter Drucker noted, a very large number of workers do both knowledge work and manual work[1]. We can say that, depending on the knowledge to be discovered, every job can require knowledge work. Below are some examples comparing the manual and cognitive demands in different professions:

-

Assembly Line Worker:

- What: The specific task to be performed, such as assembling a part.

- How: The method provided by the assembly line and the standard operating procedures.

- Why: The reason behind the task, typically embedded in the process design and not always clear to the worker.

- In this scenario, much of the required knowledge is provided by the assembly line itself, and the worker's skills are aligned with repetitive tasks that require precision and consistency. We may speculate that there is 5% of knowledge work and 95% manual work.

-

Software Developer:

- What: The specific functionalities and features to be developed.

- How: The technical implementation, which often requires learning new programming languages or frameworks.

- Why: The business rationale behind the features, which can be critical for prioritizing tasks and making design decisions.

- Unlike the assembly line worker, software developers often need to acquire both the "what" and the "how" knowledge, as it is not readily available. They must engage in continuous learning and problem-solving to fill the gaps. We may speculate that there is 95% of knowledge work and 5% manual work.

-

Pilots, Surgeons, Teachers:

- What: The specific tasks associated with their professions (e.g., flying a plane, performing surgery, teaching a class).

- How: The methods and procedures they follow, often honed through extensive training and practice.

- Why: The underlying principles and goals of their work, which they usually understand well.

- These professionals typically know most of "what" to do and "how" to do it, although there may be some missing knowledge, especially in unique or complex cases. We may speculate that there is 15% of knowledge work and 85% manual work.

This is exemplified by Margaret Hamilton's contribution to the Apollo 11 program in 1969. In the picture below to the right, we see Margaret being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama.

In the picture to the left, Margaret is standing next to part of the computer code she and her team developed for the Moon landing. What we witness is an example of the manual part of knowledge work. The software developers had to type all of those pages manually. All the knowledge went from their brains, through their fingers, and ended up as symbols on sheets of paper. The difficult and time-consuming activity in creating Moon landing software was not in typing their already-available knowledge into source code. It was in effectively acquiring knowledge they did not already have, i.e., getting answers to the questions they already had. Even more specifically, it was in discovering the knowledge necessary to make the system work that they did not know they were missing. The symbols are the tangible output of their knowledge work. The symbols are not the knowledge itself but the trace of the knowledge left on the paper.

Through these examples, it becomes evident that different professions demand varying proportions of manual and knowledge work. While some jobs embed much of the required knowledge within the tools and procedures used, others necessitate continuous learning and adaptation to bridge the gap between existing skills and the demands of the task.

Every Job Could Require Knowledge Work

Not only do different professions require different amounts of knowledge work, but the same profession, when executed by people with different levels of prior knowledge, could require a different proportion of knowledge work.

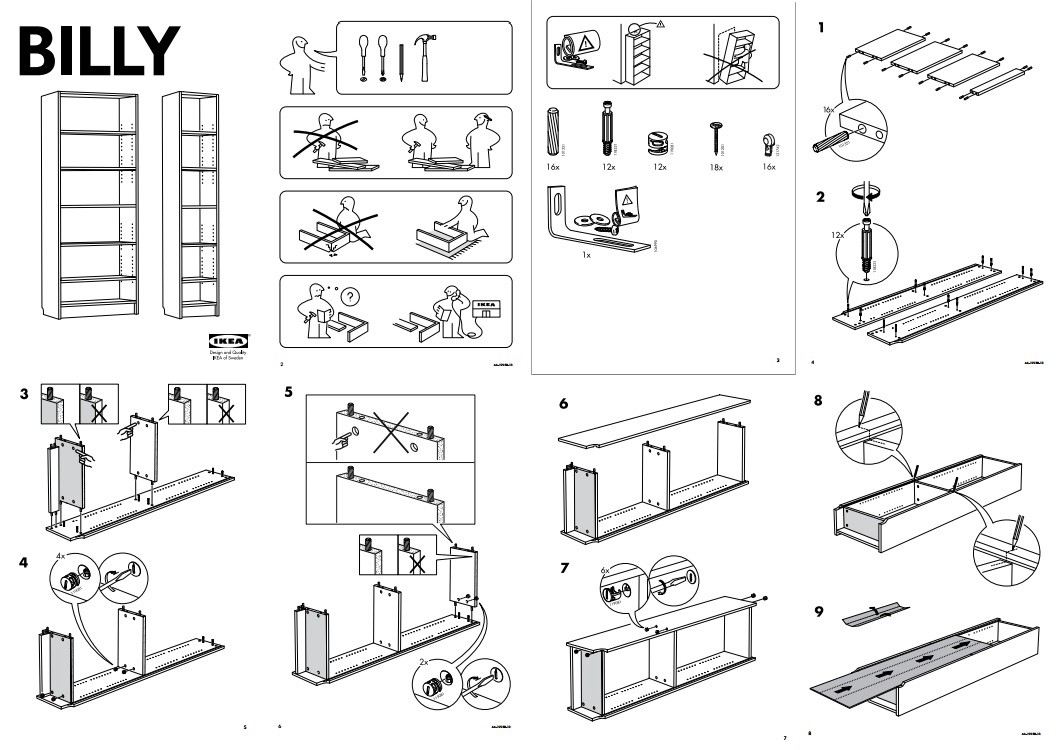

Imagine two people assembling the same model of IKEA furniture, "Billy." We know their names are Joe and Don. Don is a professional furniture assembler, while Joe is a novice assembling his first piece of furniture. Our task is to identify Joe and Don just by observing them assemble the furniture.

Many of us have experienced the frustration of assembling a Billy. The furniture arrives neatly packed in a box, but within minutes of opening it, the contents seem to have multiplied. There’s suddenly not enough space to stack all the pieces, and you struggle to keep the screws and fasteners in a neat pile. The instructions, printed without words and using only simple illustrations, can be extremely perplexing.

The first few steps go smoothly, but soon you encounter a step where everything seems to go wrong. You reread the instructions, try to fit the pieces together, but it’s not working. After multiple attempts and a chaotic room with screws rolling everywhere, you finally get the pieces to fit. As you approach the final step, you realize you’re one screw short. For 10 minutes, you search through the garbage, eventually finding the last screw—the key to finishing the job. You’re sore, tired, and mentally exhausted, having spent time asking yourself many more questions than you anticipated.

Reflecting on our own experiences, we can easily identify who finds the manual sufficient and who asks additional questions. Don, the professional, should be the one finding the manual informative enough, as his training has provided him with all the prior knowledge needed to assemble the furniture. Joe, the novice, is likely the one spending a lot of time sitting on the floor with an Allen wrench in one hand and the manual in the other, struggling to piece everything together.

The Knowledge-Centric Perspective on Work

A knowledge-centric perspective on work focuses on the knowledge that needs to be discovered. This means prioritizing the cognitive aspects of work over the manual ones. However, this does not mean we dismiss the importance of managing the manual parts of human work.

The manual-centric perspective is equally valid and well-researched. It addresses the physical and procedural aspects of tasks, ensuring efficiency and effectiveness in execution.

When combined, the knowledge-centric and manual-centric perspectives provide a comprehensive and holistic view of all human activities. The beauty of this approach is that the two perspectives do not conflict; rather, they complement each other. Each offers a unique standpoint, and together, they provide a fuller, more complete picture of human work.

Conclusion

In summary, knowledge work involves the cognitive effort to bridge the gap between what is known and what needs to be known, and it is essential in all professions. While traditionally associated with information-heavy roles like software development, knowledge work is present in all jobs to varying degrees, depending on the balance between required and prior knowledge.

Understanding that every job comprises both cognitive and manual work highlights the value of both perspectives. The knowledge-centric and manual-centric viewpoints do not conflict but rather complement each other, offering a comprehensive understanding of human work.

In recognizing the value of both knowledge work and manual labor, we can appreciate the diverse skill sets and intellectual engagements required across various professions. This balanced view helps foster a more inclusive and accurate representation of the modern workforce, highlighting the interconnected nature of all human work.

How to cite:

Bakardzhiev D.V. (2024) What is Knowledge Work : Definition and examples https://docs.kedehub.io/kede/what-is-knowledge-work.html

Works Cited

1. Drucker , Peter F, “Knowledge-Worker Productivity: The Biggest Challenge,California Management Review, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 79–94, Jan. 1999, doi: 10.2307/41165987.x

2. Lundvall, B. Å and Johnson, B. (1994), “The learning economy”, Journal of Industry Studies, Vol. 1, No. 2,December 1994, pp. 23-42.

Getting started