Knowledge Discovery Efficiency (KEDE) and Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety

Abstract

We address Real-world applications of Ashby's Law by adopting Ashby's strict black-box perspective: only external behaviour is observable. First we define the multi-staged selection process of narrowing down and selecting the appropriate response from the set of alternative responses as the Knowledge Discovery Process. We then label H(X|Y) as the knowledge to be discovered, which is the gap in internal variety that had to be compensated by selection. This quantifies how much disorder the regulator still permits and, conversely, how close the system comes to meeting Ashby's requisite-variety condition. In information-theoretic terms, perfect regulation requires H(X|Y) = 0. Then we quantify the knowledge to be discovered H(X|Y) based on the observable outcomes E. Building on this result, we generalize Knowledge-Discovery Efficiency (KEDE) - scalar metric that quantifies how efficiently a system closes the gap between the variety demanded by its environment and the variety embodied in its prior knowledge. KEDE operationalises requisite variety when internal mechanisms remain opaque, offering a diagnostic tool for evaluating whether biological, artificial, or organisational systems absorb environmental complexity at a rate sufficient for effective regulation. Finally we present applications of KEDE in diverse domains, including typing the longest English word, measuring software development, testing intelligence, basketball game, assembling furniture, and speed of light in medium.

1. Introduction

The Law of Requisite Variety, formulated by W. Ross Ashby, states that for a system to effectively regulate its environment, it must have at least as much variety/complexity as its environment. This principle is foundational in disciplines such as cybernetics, control theory, and machine learning.

The concept of requisite variety has since been applied across diverse domains, including organizational theory, ecology, and information systems. It underscores the necessity for systems to adapt to environmental complexity in order to maintain stability and achieve intended outcomes.

Real-world attempts to apply Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety face three persistent obstacles. (i) Combinatorial explosion: enumerating all relevant states of a system and its environment quickly becomes intractable, especially when hidden or unmeasured variables are present. (ii) Dual control dilemma: a regulator must simultaneously amplify its own control variety and attenuate external variety—an optimization that is delicate in multiscale, hierarchical, and time-varying settings such as digital ecosystems or military command structures. (iii) Resource constraints: limited data, computational power, and organisational capacity often preclude sophisticated control architectures. Existing remedies—markup-language state catalogues, iterative multidimensional sampling, and distributed self-organising controllers—mitigate but do not eliminate these limitations.

In section 2, we provide a detailed overview of Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety, including its mathematical formulation and implications for system regulation. We also discuss the present day understanding of residual variety and its significance in the context of Ashby's Law. In section 3, we discuss the challenges of applying Ashby's Law to real-world systems, including combinatorial explosion, dual control dilemma, and resource constraints. We propose a solution to these challenges by treating the system as a black box, observing probability of successful outcomes to disturbances, and estimate the gap in its internal variety based on that. In section 4, we start establishing the solution by introducing the Knowledge Discovery Process, which is narrowing down and selecting the appropriate response from its set of alternative responses. We then label H(X|Y) as the knowledge to be discovered, which is the gap in internal variety that had to be compensated by selection. In section 5, we show how to quantify the knowledge to be discovered H(X|Y) based on the observable outcomes E. In section 6, we generalize the Knowledge-Discovery Efficiency (KEDE) - scalar metric that quantifies how efficiently a system closes the gap between the variety demanded by its environment and the variety embodied in its prior knowledge. Finally, in section 7, we explore applications of KEDE in various domains, demonstrating its utility as a diagnostic tool for evaluating system performance and adaptability.

2. The Law of Requisite Variety

In practice, the question of regulation usually arises in this way: The essential variables E are given, and also given is the set of states S in which they must be maintained if the organism is to survive (or the industrial plant to run satisfactorily). These two must be given before all else. Before any regulation can be undertaken or even discussed, we must know what is important and what is wanted. ... It is assumed that outside considerations have already determined what is to be the goal, i.e. what are the acceptable states S. Our concern...is solely with the problem of how to achieve the goal in spite of disturbances and difficulties[1].

Given a set of elements, its variety is the number of elements that can be distinguished. Thus the set {g b c g g c } has a variety of 3 letters. Variety comprises any attribute of a system capable of multiple 'states' that can be made different or changed.

The Law of Requisite Variety, formulated by W. Ross Ashby states that:

For a system to effectively regulate its environment, it must have at least as much variety as its environment

Ashby's Law is held true across the diverse disciplines of informatics, system design, cybernetics, communications systems and information systems.

Mathematical Formulation

In Ashby's terms, we can think of the system as a transducer:

Where:

- D be the set of disturbances, representing the possible states of disturbances that a system may experience.

- R be the set of responses, representing the possible regulatory actions that counteract disturbances.

- O be the set of realized outcomes, representing the possible outcomes that can result from the disturbance-response pairs (D, R), without any implication of desirability. D x R → O is the fixed transition rule of the environment.

- E be the set of values / essential-variable states that the system aims to achieve, induced by a valuation mapping v : O → E. The scale of values in E may be as simple as the 2-element set {good, bad}, and is commonly an ordered set.

Some subset of acceptable outcomes of E can be defined as the goal G ⊂ E[8]. Given the goal G then the inverse mapping of this subset will define, over O, the subset S of “acceptable outcomes”. Thus is defined a relation equivalent to “ri, as response to di, gives an acceptable outcome s ∈ S”[8].

This can be represented as a Table of Outcomes (T) where:

- T be the pay-off matrix, i.e. a fixed mapping T : D x R → O or the fixed transition rule of the environment.

- Rows represent disturbances D

- Columns represent regulatory responses R

- Entries represent realized outcomes O = {o11, o12, o13, ..., o21, o22, o23, ..., o31, o32, o33, ..., ...} in the cells of the matrix, O = {o} = T(d,r) ∈ O, where d is a disturbance and r is a regulatory response.

| T | R | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r₁ | r₂ | r₃ | ... | ||

| D | d₁ | o₁₁ | o₁₂ | o₁₃ | ... |

| d₂ | o₂₁ | o₂₂ | o₂₃ | ... | |

| d₃ | o₃₁ | o₃₂ | o₃₃ | ... | |

| d₄ | o₄₁ | o₄₂ | o₄₃ | ... | |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | |

The Table of Outcomes (T) is a fixed, structured space of possibilities, or the fixed transition rule of the environment, which directly determines the essential variables E. In simplified analyses, O and E are sometimes conflated, but they are conceptually distinct. In the deterministic pay-off-matrix case, the environment is the fixed function T : D x R → O, and evaluation is v : O → E. If D and R are treated as random variables, then the induced conditional distribution is P(E | D, R) determined by E = v(T(D,R)).

The regulator's accumulated structure M is its learned law of action. In the deterministic case, M : D → R. In general (learning, uncertainty), treat it as a policy P(R | D), i.e. how probability mass is allocated across responses for each disturbance.

Across time, the learning object M is not fixed. If the table O is the space of possibilities, then M is the mechanism that induces a measure over possible paths through that space.

Learning and rework do not alter the structure of the Table of Outcomes T. Instead, they modify the regulator's accumulated structure M. Changes in M alter which disturbance-action pairs become more or less probable and therefore how the system's realized trajectories are distributed over the table O.

Rework corresponds to a revision accumulated structure M: probability mass is shifted away from previously selected or ineffective responses and reassigned to alternative responses for the same disturbance. Thus, the Table of Outcomes (T) remains a fixed space of possibilities, while learning and rework change only the regulator's induced distribution of trajectories through that space, not the space itself.

Each input from D is transformed via selection into a response

,

which is then processed to produce an outcome

.

which is then evaluated as

,

which is the essential variable that the system aims to achieve, induced by a valuation mapping v : O → E.

If R does nothing, i.e. keeps to one value, then the variety in D threatens to go through O to E, contrary to what is wanted. It may happen that O, without change by R, will block some of the variety and occasionally this blocking may give sufficient constancy at E. More commonly, a further suppression at E is necessary; it can be achieved only by further variety at R.

Under idealized assumptions, Ashby showed that a lower bound on the achievable variety in the outcomes is given by the smallest variety that can be achieved in the set of actual outcomes cannot be less than the quotient of the number of rows divided by the number of columns.

Where:

- V(D) = variety in the disturbances

- V(R) = variety in the regulatory responses

- V(E) = variety in the essential variables

This inequality shows that the variety in the essential variables cannot be reduced below the division between the variety in the disturbances and the variety in the regulatory responses.

Perfect regulation here means deterministic essential variable, not merely acceptable performance. For perfect regulation, we need V(E) to be stable or close to 1 (only one possible value) i.e.

The law reflects a fundamental insight: control is about the ratio of disturbances to regulatory responses, not just their arithmetic difference.

Information-Theoretic Formulation

All acts of regulation can be related to the concepts of communication theory by noticing that the “disturbances” correspond to noise, and the “goal” is a message of zero entropy, because the target value E is constant. Thus, the law of Requisite Variety says that R 's capacity as a regulator cannot exceed R 's capacity as a channel of communication.

The variety is measured by the logarithm of its value. If the logarithm is taken to base 2, the unit is the bit of information. Applying this to Ashby's Law we get:

In practice, we use the Shannon information entropy, denoted by H. For a quantifiable variable, entropy is just another measure of variance. If we assume equiprobable disturbances/responses and treat variety as cardinality, then H reduces to , yielding:

Ashby's Law can be interpreted as a cybernetic analogue of Shannon's "Noisy channel coding theorem" which states that communication through a channel that is corrupted by noise may be restored by adding a correction channel with a capacity equal to or larger than the noise corrupting that channel. The disturbance D, which threatens to get through to the outcome E, clearly corresponds to the noise; and the correction channel is the system R, which is supposed to restore the outcome E[8].

Ashby's law can thus be reformulated clearly:

The information-processing capacity (entropy) of a control system must be at least as large as the information (entropy) in the system it regulates.

It has been shown shown that the law of requisite variety can be extended to include knowledge or ignorance by simply adding this conditional uncertainty term[31] When buffering is present, part of the environmental variety is absorbed passively before reaching the regulator. This reduces the effective disturbance entropy by an amount K, which is the buffering capacity:

Where:

- H(E) is the residual variety i.e. the realized essential-variable distribution, not the size of the set E

- H(R) is the entropy of the regulator, representing its information-processing capacity.

- H(D) is the entropy of the disturbances, representing the complexity of the environment.

- H(R|D) is the conditional entropy of the regulator given disturbances, representing the lack of requisite knowledge i.e. the ignorance of the regulator about how to react correctly to each appearance of a disturbance D. Only a regulator that knows how to use the available regulatory variety H(R) to react correctly to each disturbance D will reach the optimal result of regulation,

- K is the buffering capacity measured in bits of disturbance variety absorbed before reaching the regulator. Buffering is the passive absorption or damping of disturbances i.e. the amount of noise that a system can absorb without requiring an active regulatory response.

A necessary but not sufficient condition for effective control (to make H(E) small) is: . Sufficiency additionally requires

Successful (essential) outcomes E do not depend solely on the variety of responses H(R) available to a regulator R; the system must also know which response to select for a given disturbance. Effective compensation of disturbances requires that the system possess the ability to map each disturbance to an appropriate response from its repertoire. The absence or incompleteness of such knowledge can be quantified using the conditional entropy H(R|D)[31]. In other words, H(R|D) measures how much the regulator R lacks the requisite knowledge to match responses to disturbances. In the absence of such requisite knowledge, the system would have to select responses, until eliminating all disturbances. Thus, merely increasing the response variety H(R) is not sufficient; it must be complemented by a corresponding increase in selectivity, that is, reduction in H(R|D) i.e. increasing knowledge. H(R|D) = 0 represents the case of no uncertainty or complete knowledge, where the action is completely determined by the disturbance. This requirement may be called the law of requisite knowledge[29].

H(R|D) reminds us that response alone is not sufficient: if the regulator does not know which response is appropriate for the given disturbance, it can only try out regulatory actions at random, in the hope that one of them will be effective and that none of them would make the situation worse. The larger the H(R|D), the larger the probability that the regulator would choose a wrong regulatory response, and thus fail to reduce the variety in the outcomes H(E). Therefore, this term H(R|D) has a “+” sign in the inequality: more uncertainty (less knowledge) produces more variation in the essential variables E[54].

To achieve control, the regulator R must possess sufficient information-processing capacity (entropy) such that the following is achieved:

In other words, the complexity of the environment D can not exceed that of the system R, which means the system R fully matches the environment D[7].

Since the law simplifies to:

The mutual information I(R:D) represents the requisite knowledge of the regulator R about how to react correctly to each disturbance D, i.e. the amount of regulatory variety that is effectively correlated with and therefore absorbs the variety in the disturbances. Such knowledge may be realized structurally as the regulator's learned law of action M represented by a mapping M: D → R , by which disturbances are mapped to regulatory responses[54]. The mutual information I(R:D) quantifies how much of the regulator's learned law of action M: D → R effectively couples disturbances to responses, while the remaining uncertainty H(R|D) quantifies the lack of requisite knowledge[29].

3. Core challenges in applying Ashby's Law to real systems

We conducted a literature review aimed at identifying the primary challenges and limitations associated with applying Ashby's Law in real-world systems.

A central challenge that emerges is the measurement of variety. In most of the reviewed literature, the concept of variety is either poorly defined or not explicitly measured, resulting in ambiguity and potential misinterpretation of the law's implications. Key obstacles to effective measurement include:

- The direct measurement of variety is fundamentally incomputable for all but the simplest systems [14].

- Hidden variables introduce uncertainty and complicate measurement efforts [15].

- Trade-offs often arise between variety at different scales [16].

- A combinatorial explosion occurs when attempting to enumerate all possible system states [15,16].

- Resource limitations constrain the feasibility of comprehensive measurement [20].

- Environmental complexity is frequently “unknowable,” preventing complete assessment [25].

- Most studies lack explicit or standardized methods for quantifying variety [14,17'-20,25,27].

- Existing approaches often lack rigorous quantitative validation [17].

Several measurement methods have been proposed, including:

- Markup language-based variety estimation [18],

- Iterative sampling techniques [21],

- Entropy and determinism metrics to evaluate communication complexity, where greater variety was correlated with improved effectiveness [22],

- Social network and cluster analysis to assess resilience [23], and

- Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) for capturing organizational complexity [24].

In addition, a subset of studies estimate variety through observed performance rather than structural attributes. Notable examples include:

- Communication-based performance measures, employing determinism metrics to evaluate repeatable patterns in team behavior [22];

- Team performance assessments, using task-based surveys to evaluate an organization's risk-handling capabilities [23];

- Leadership behavior analysis, based on actual behavioral responses to simulated scenarios [26]; and

- Relative performance comparisons, assessing organizational effectiveness across contexts using perception-based rather than absolute metrics [14].

While these performance-based approaches provide practical insights, they often rely on subjective or indirect indicators of variety, which may introduce biases and limit their generalizability. For example, performance outcomes may fail to account for hidden variables or the underlying complexity of the system [15]. Moreover, these approaches remain underrepresented in the literature, where structural and theoretical analyses still dominate.

In summary, although numerous methods for measuring variety have been proposed, no single comprehensive or universally accepted solution has emerged. Quantification remains a persistent challenge in the application of Ashby's Law to complex real-world systems.

Solution

These challenges significantly hinder the practical application of Ashby's Law. Whether considering a human, an AI model, or an organization, we are typically limited to observing external behavior rather than internal mechanisms—unless we are able to "open the box."

Ashby himself emphasized that all real systems can be considered black boxes. He argued that while black boxes mimic the behavior of real objects, in practice, real objects are black boxes: we have always interacted with systems whose internal workings are, to some extent, unknown.

This leads to what Ashby termed the black box identification approach [2], which involves:

- Perturbing the system by applying external disturbances,

- Measuring the system's responses to these perturbations, and

- Inferring the internal variety or capacity from the observed input-outcome relationships.

In most practical scenarios, we are only able to observe the outcomes of a system. These observable outcomes can be used to infer bounds on the system's internal variety—specifically, the extent of variety it must possess or lack in order to exhibit the observed behavior.

We propose such an approach: to treat the system as a black box, observe the probability of successful outcomes to disturbances, and estimate the gap in its internal variety based on that. Let E denote the event that the system gives an response to disturbance D, and let R be the regulator's action. In information-theoretic terms, perfect regulation requires H(R|D) = 0[31]. Using our novel information-theoretic estimator, empirical estimates of P(E=1) are used to quantify H(R|D) in bits of information. This quantifies how much disorder the regulator still permits and, conversely, how close the system comes to meeting Ashby's requisite-variety condition.

4. Knowledge Discovery Process

The process of selection may be either more or less spread out in time. In particular, it may take place in discrete stages. What is fundamental quantitatively is that the overall selection achieved cannot be more than the sum (if measured logarithmically) of the separate selections. (Selection is measured by the fall in variety.) 13/17[2]

Ashby's selection in design and regulation via requisite variety are structurally identical: they describe how constraints (or regulation) reduce the variety of possible outcomes from an initial space. in Ashby, constraints, tests, feedback, rules, observations are all selection mechanisms that reduce variety.

Ashby[13/15 [2]] measures the amount of selection in bits as:

Where

- σ is the amount of selection (the amount by which the variety is reduced) or the information gained, i.e., how much the uncertainty has been reduced.,

- Vbefore is the variety before the selection i.e. before a constraint (filter, decision, control action) is applied, and

- Vafter is the variety after the selection i.e after the constraint is applied.

From here on, we treat "variety in bits" as Shannon entropy i.e., using the distribution over possibilities. If alternatives are equiprobable, this reduces to Ashby's counting form.

Thus every time we introduce a rule or a constraint we throw away some of the possibilities and gain information equal to the logarithm of that reduction:

- “What fraction of possibilities remains?” '- that is Vbefore / Vafter

- “How many bits of information does this represent?” '- that is σ = log2(Vbefore/Vafter)

Rather than a single act, selection is often a multi-stage process consisting of k successive selections from a range of possibilities[2][4]. Each selection stage reduces the set of admissible alternatives, progressively transforming an initial space of variety into a more constrained set of alternatives with the goal to produce an acceptable outcome. Formally, this process can be understood as a sequence of k uncertainty-reducing operations, where each selection narrows the possibility space and thereby decreases entropy. Mathematically we have:

The total selection is the sum of the amount of selections achieved at each stage because logarithms turn multiplications of ratios into additions:

The total process therefore consists of k such selections, each conditioned on the result of prior selections. Reductions add only for nested/refining partitions (each stage refines the previous stage's partition of possibilities). If two stages constrain the same dimension in overlapping ways, we must count the second stage's reduction relative to the first, not from the original variety. The number of selections k thus characterizes the depth of the selection process and corresponds to the number of distinct uncertainty-reducing decisions required to reach the final state.

We refer to the multi-stage process of narrowing down and selecting the response from its set of alternative responses to produce an acceptable outcome as a Knowledge Discovery Process.

We can say that we've got "it from bit" - a phrase coined by John Wheeler. "It from bit" symbolizes the idea that every item in the physical world has knowledge as an immaterial source and explanation at its core[6].

So far we have used Ashby's notation for disturbances D and regulation responses R. At this point disturbances are denoted by Y and responses by X. The table below aligns Ashby's language of regulation with Shannon's information-theoretic quantities by showing that both describe the same process: the progressive reduction of uncertainty about which action will succeed.

| Ashby term | Symbol | Shannon / Information-theoretic term | Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disturbance (observed at decision time) | D | Conditioning variable (given side-information) | Y |

| Regulator response emitted (selected action) | R | The regulator's selected response (a random variable) | X |

| Lack of requisite knowledge of the regulator about which response will produce an acceptable outcome given a disturbance | H(R|D) | Conditional entropy of the regulator's selected response, given the observed disturbance | H(X | Y) |

| Selection signals (tests, observations, feedback, constraints, rules, partial executions) | Z1, Z2, …, Zk | Auxiliary information sources that reduce uncertainty about which response X is acceptable for a given Y | Z1, Z2, …, Zk |

| Residual variety after the i-th selection stage | V(R | D, Z1, …, Zi) | Conditional entropy remaining after i-th selection stage | H(X | Y, Z1, …, Zi) |

| Selection achieved at stage i (reduction in variety due to one constraint) | log2 Vbefore / Vafter,i | Conditional mutual information acquired at stage i | I(X ; Zi | Y, Z<i) |

| Residual variety after k selection stages | V(R | D, Z1, …, Zk) | Conditional entropy of the regulator's selected response, given the observed disturbance and k selection signals | H(X | Y, Z1, …, Zk) |

| Total selection achieved (successful adaptation) | log2 Vbefore / Vafter | Total mutual information acquired through all selection stages | I(X ; Z1, …, Zk | Y) |

Multi-stage selection

We denote the amount of selection achieved at each stage i as: . When mapping one stage of selection with one selection signal Zi we have:

As selections accumulate, the remaining uncertainty shrinks. The total amount of selection Ashby describes is mathematically identical to the total mutual information accumulated across stages.

Shannon's chain rule for mutual information is:

If stages share information or impose overlapping constraints, summing their marginal “reductions” overcounts. The correct decomposition credits each stage only for the reduction of residual uncertainty left by previous stages. Therefore the per-stage contributions must be conditional (incremental) to avoid double counting, because stages may share information or constrain overlapping parts of X. The correct staged accounting is the mutual-information chain rule over the selection signals Z:

After k selections we have:

Given the success criterion of determining the response X for a given disturbance Y, Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety for a staged selection process is:

Or equivalently, the sum of the bits removed by selection by every stage must at least equal the bits of uncertainty injected by the original range of possibilities or by disturbances.

Regulation

An episode represents a specific interaction or event in time, characterized by a structure designed for learning and pattern recognition:

- A disturbance (Y): An external stimulus, perturbation, or environmental input that acts upon the system.

- A response (X): The system's internal action or selection made or outcome generated in response to the disturbance Y.

- A within-episode sequence of evidence (Z1, Z2, …, Zk): A sequence of constraints, tests, feedback signals, or rules that are applied to the system in response to the disturbance.

- The system's internal structural coupling (M): A mapping of disturbances to responses.

- A Start Time (tstart): The time at which the window starts (e.g. the start of the first episode).

- A End Time (tend): The time at which the window ends (e.g. the end of the last episode).

A disturbance Y is fixed and fully observed at episode start and is treated as given. All remaining uncertainty is only about which response X will be selected; subsequent Z is evidence about X, not new disturbance info. This initial uncertainty is the lack of requisite knowledge, measured as the initial conditional entropy H(X|Y). The system then applies a sequence Z1, Z2, …, Zk of constraints, tests, feedback signals, or rules, each of which removes some possibilities and therefore reduces the lack of requisite knowledge. In Ashby's terms this is “selection”; in Shannon's terms each stage i contributes conditional mutual information I(X ; Zi | Y, Z<i). “Non-outcome time” is entirely spent on discriminating information about X for the current episode, and outcome emissions are atomic and don't hide extra selection. “episode closes with an acceptable outcome” event occurs only after the regulator has already fixed the exact response X (so the closure event certifies that the episode's X has been identified/committed). Therefore, the episode closes with an acceptable outcome event certifies that the episode's X has been identified/committed.

Let Mt be the system's internal stored structural coupling (mapping) at the start of episode t. In Ashby's terms, M is not a separate object but the regulator's law of action i.e. the learned functional relation by which disturbances are mapped to responses to produce acceptable outcomes[54]. In contrast, the Table of Outcomes (T) is a fixed strucured space of possible outcomes and it specifies what outcome would result from each disturbance'-response pair .

For each episode t in a window, the stored structural coupling (mapping) Mt is treated as a parameter (not a random variable): Therefore we do not write entropies or mutual informations “conditioned on Mt”. Instead, we write them as quantities induced by the mapping:

When we need a quantity that also depends on within-episode evidence Z, we use the same convention, e.g. It(X;Z|Y) means IMt(X;Z|Y).

Here "induced by Mt" means that the distribution we use to compute entropy is the one produced by the policy/model state Mt. This aligns with the “ignorance term” H(D|R) changing under adaptation (variable structure) without treating the structure itself as a random variable inside the episode.

Regulation uses staged evidence to eliminate uncertainty within an episode t, where k is the number of selection signals within the episode t. During an episode staged selection supplies until the response X is effectively determined:

Multiple acceptable responses (compatibility note).

In this theory, X denotes the specific response actually selected/emitted by the regulator (a random variable), not the equivalence class of acceptable responses.

Therefore, even if multiple responses x∈X are acceptable for a given disturbance y∈Y, H(X|Y) do not measure “uncertainty about success.”

H(X|Y) measures the remaining uncertainty about which response will be emitted under the regulator's current policy Pt(X|Y).

Learning can still drive H(X|Y) toward 0 by structuralizing tie-breaking.

Learning (across episodes)

Regulation can use within-episode evidence Z to determine the response X for a given disturbance Y during an episode t. Learning makes that success persistent by updating the stored structural coupling (mapping) M so future episodes start with less esidual uncertainty about which response will be selected for the same class of disturbances.

Learning Axiom (Structural Knowledge Accumulation). A system is said to learn (in the structural-coupling sense) if and only if the within-episode evidence stream Zt = (Zt,1, …, Zt,kt) is incorporated into an updated mapping Mt+1 = Update(Mt, Zt), such that for subsequent encounters with the same class of disturbances Y, the induced lack of requisite knowledge decreases:

In words: learning means that the next episode starts with less uncertainty than the current one started with, because the mapping Mt+1 was updated. (Note: this does not in general imply that I(X;Y) must increase unless additional assumptions are made about the marginal distribution of X; we keep the learning definition anchored to the decrease in Ht(X|Y).)

Strong Learning Assumption (Posterior-Becomes-Prior Rule). A stronger form of learning is obtained when the system stores and reuses, without loss, the uncertainty reduction achieved within episode t. For a stable task class, we then assume:

- the same task class or disturbance semantics across episodes,

- successful retention of the within-episode discoveries,

- reuse of that stored structure in later episodes,

- no intervening forgetting or context drift that would invalidate the stored coupling.

Corollary (Complete Adaptation under Strong Learning Assumption). Under the Posterior-Becomes-Prior Rule, repeated successful adaptation drives the residual lack of requisite knowledge toward zero for the task class: . Equivalently, in the limit, the response becomes effectively determined by the disturbance: . This is the state of complete adaptation for the task class: no further within-episode discovery is required in order to determine the response.

Clarification (Strong Learning Assumption). The weak learning axiom is sufficient to define learning. The strong form is only needed because in what follows our model will assume that within-episode discoveries are fully carried forward as next-episode prior structure.

Rework, retraction, and net learning

A mapping update may include both the the addition of improved structure and withdrawal of previously stored structure. These internal components must be distinguished from observable rework and from the net epistemic effect of the update.

Let Mt be the regulator's stored structural coupling at the start of episode t, and let Mt+1 = Update(Mt, Zt) be the mapping after the episode's evidence Zt has been incorporated. We do not assume any particular memory mechanism (overwrite, patching, versioning, or full replacement). We track only the effect of the update on the regulator's induced coupling measures.

Under the mapping Mt, define:

Three distinct notions

1. Observable rework. Rework is any externally visible correction, undo, replacement, deletion, or repair of prior commitments. Observable rework is defined at the level of artifacts and execution behavior.

2. Internal retraction and accretion. A mapping M update may contain:

- a retraction component: previously stored structure is withdrawn, weakened, or invalidated, and

- an accretion component: new or improved structure is added or strengthened.

These are internal aspects of the update of M. They should not individually be identified with “negative learning” or “positive learning”. In particular, removing false structure is often part of successful learning.

3. Net learning. Learning is evaluated by the net change in the induced coupling measures after the whole update has been completed, not by whether some internal fragment was deleted.

Net learning criterion

Define the net change in stored requisite coupling:

Equivalently, under the uncertainty view:

Then:

- Net positive learning iff ΔtI > 0 (equivalently, a net decrease in lack of requisite knowledge under the chosen uncertainty view).

- Zero net learning iff ΔtI = 0.

- Net negative learning iff ΔtI < 0, i.e. the final mapping is worse than the initial one with respect to stored requisite coupling.

Thus, negative learning is reserved for net worsening. It should not be used merely because part of the update involved deletion or withdrawal of prior structure.

Exact knowledge ledger of net change

For knowledge accounting, define the positive and negative parts of the net coupling change:

By definition, the net ledger is exact:

This ledger records only the net epistemic effect of the update. It does not assert that the update process itself consisted of a pure gain or a pure loss. A single episode may contain both correction of prior commitments and improved learning, yet still end with Gt > 0.

Why rework is not the same as negative learning

An episode may contain observable rework and still produce net positive learning. For example, a software developer may correct a previously committed line of code by deleting a wrong symbol and replacing it with the correct one. This is clearly rework at the artifact level. But if the correction improves the developer's future mapping from disturbance to response, then the episode yields net positive learning, not negative learning.

Accordingly:

- Rework + net positive learning is possible.

- Rework + zero net learning is possible.

- Rework + net negative learning is also possible.

Therefore, observable rework does not by itself imply ΔtI < 0.

Observable rework as external evidence

Operationally, we usually cannot observe the internal decomposition of the mapping update. What we can observe is whether the window contains explicit undo/repair commitments. Let Wt denote the number of such observable rework outcomes in window t.

A nonzero Wt > 0 is evidence that correction activity occurred. It may indicate that some prior structure was inadequate and that the update contains a retraction component. But it is not sufficient to conclude that the episode produced net negative learning. That conclusion requires the stronger condition ΔtI < 0.

In summary:

- Rework is an observable artifact-level phenomenon.

- Retraction / accretion are internal components of a mapping update.

- Learning is evaluated only by the net change in stored requisite coupling or, equivalently, by the net change in lack of requisite knowledge.

Defining Knowledge to be Discovered

Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety concerns capacity: the regulator must have a sufficiently large repertoire of possible responses[1]. Heylighen's Law of Requisite Knowledge adds the missing condition for effective regulation: it is not enough to have many possible actions; the regulator must know which action to select for the given disturbance. Otherwise, increased action variety increases the chance of choosing the wrong action, forcing trial-and-error selection[29].

In information-theoretic terms, this “knowing which action to select” is exactly the reduction of uncertainty about the response X once the disturbance Y is observed. That uncertainty is the conditional entropy H(X|Y).

Knowledge To Be Discovered. We define Knowledge To Be Discovered as the conditional entropy H(X|Y): the expected uncertainty about which response(s) will achieve success, given that the disturbance is known. Operationally, it is the amount of selection (in bits) that must still be supplied in order to determine a successful response.

Knowledge to be discovered H(X|Y) is Ashby's ignorance term H(R|D) (same mathematical object), and it appears additively in the lower bound on residual outcome entropy.

Thus, Knowledge To Be Discovered is the precise difference between the action variety available and the coupling/selectivity actually achieved:

- H(X) is the regulator's variety of responses available to be selected, or the prior knowledge.

- I(X;Y) is the regulator's requisite knowledge: how much the disturbance actually informs the choice of action, or the required knowledge.

- H(X|Y) is the remaining uncertainty after the disturbance is known, i.e. the lack of requisite knowledge, or the knowledge to be discovered.

Requisite knowledge is not an independent thing but the total selectivity actually available at decision time makes H(X|Y) small which can be stored structure M or online evidence Z:

- Offline (stored) coupling: learning updates the mapping M so that future stages start with higher It(X;Y) and therefore lower Ht(X|Y).

- Online (within-stage) selection: evidence Z (tests, observations, constraints) supplies additional conditional information I(X;Z|Y), driving H(X|Y,Z) toward 0 during regulation.

In the ideal case of complete adaptation for the task class, the regulator's selectivity is perfect: H(X|Y) = 0 (the response is effectively determined by the disturbance). If multiple responses are acceptable, we will replace X with the equivalence class of acceptable actions or measure success directly via the goal variable.

This yields the intended conceptual pairing:

- Residual variety H(E): what remains uncontrolled in outcomes.

- Knowledge To Be Discovered H(X|Y)≡H(R|D): what remains undetermined about which action succeeds, given the disturbance.

This framing suggests that reducing "knowledge to be discovered" is a pathway to reducing "residual variety" - which is exactly the cybernetic insight that better information about disturbances enables better control. It emphasizes the constructive, learning-oriented aspect of cybernetic systems rather than just their current limitations.

5. Quantifying Knowledge To Be Discovered

How is the desired regulator to be brought into being? With whatever variety the components were initially available, and with whatever variety the designs (i.e. input values) might have varied from the final appropriate form, the maker Q acted in relation to the goal so as to achieve it. He therefore acted as a regulator. Thus the making of a machine of desired properties (in the sense of getting it rather than one with undesired properties) is an act of regulation[2].

We estimate the knowledge to be discovered operationally from externally observable execution counts — anchored capacity N, outcomes O and their corresponding values E, and (optionally) wasted commitments W, without observing disturbances Y, responses X, evidence Z1, Z2, …, Zk or the internal selection process directly. We focus on the case where regulation is eventually successful, i.e. the knowledge to be discovered eventually becomes 0.

Because we only observe episode-closing acceptable outcomes S, our estimator is not estimating an “environmental” equivocation. It's estimating the regulator-induced equivocation via a work-to-bits proxy, under the following assumptions:

- Each non-outcome unit delivers at most 1 discriminating bit about which x will be emitted,

- There is no hidden selection inside outcome emission,

- Y is known at episode start,

- The episode closes only once X is fixed.

That means our operational estimator is fundamentally about: Ht(X | Y) as implemented by the regulator’s actual process, not the task’s acceptability structure.

Clarifying “outcomes” vs. “activity” (episode-closure). In this model an outcome is defined operationally as a episode-closing commitment: an externally visible event that terminates the search for one disturbance-response episode. It is not “any produced artifact” or “any activity.” In software it might be a merge/accept/release; in other domains it might be an approved artifact, a published paragraph, a signed decision, etc. The theory depends only on having a consistent, externally observable episode-close event.

Clarifying “rework” (in-model). Rework is any externally observable behavior in which previously produced artifacts are revised, undone, deleted, replaced, or corrected due to new evidence (e.g. failing tests, defects, requirement changes, reversals, rollbacks). Rework is observable through external change signals such as deletions, reversions, churn, reopened items, or corrective follow-up actions. Cybernetically: rework is capacity spent on revising prior episode-closing commitments, which reduces marginal episode-closure per unit capacity because the system revisits and repairs earlier choices instead of closing new episodes.

Here are the assumptions our operational model is based on:

-

Scope of the observed outcome stream.

The operational model does not track the full Ashby outcome space. It tracks only those episode-closing commitments whose realized outcomes are counted, by the operational ledger, as acceptable closures relative to the goal criterion. In Ashby’s terms, this is the acceptable-outcome slice of the broader outcome table, not the whole table. -

Observed disturbance.

Each episode begins with an observed disturbance realization .

During that episode, is treated as fixed and fully observed. Thus the within-episode uncertainty is not about which disturbance occurred, but about which response must be selected. -

Response variable.

For a given disturbance , the regulator faces a finite candidate response set .

The random variable denotes the specific response that will be finalized/emitted in that episode. It does not denote the whole equivalence class of acceptable responses, and it is not identical to the closure indicator. -

Acceptability, response, and closure are distinct.

The model keeps separate:- the selected response ,

- the acceptability criterion induced by the goal/valuation layer,

- the observed closure event recorded in the execution stream.

-

Shared execution channel.

There is a single shared execution channel with finite window capacity . Time is partitioned into atomic intervals. In the base model, each interval contains exactly one atomic action. No parallel channels, batching, or idle intervals are assumed. -

Binary selection units.

Any interval that does not contain an episode-closing commitment is treated as one binary discriminating selection step. One such step contributes at most one bit of information relevant to fixing given . If a real-world test yields more than one bit, it is represented as multiple counted binary units. This is the operational bridge from staged selection to question-depth. -

No hidden selection inside closure.

An episode-closing commitment is atomic at the observation level. It records that the episode has closed; it does not hide additional uncounted selection work inside the same interval. -

Closure occurs only after response fixation.

Episode closure occurs only after the regulator has already fixed the episode’s selected response . Therefore a counted closure event certifies that the search for that episode has terminated with a finalized response. -

Binary event-type indicator.

Let Bt ∈ {0,1}, t = 1...N be the binary event-type indicator over the atomic intervals in the observation window, defined by: is an event-type indicator only. It is not the response variable, not a success probability, and not a value of the essential variable.

The key idea is that the regulator's capacity to respond correctly is not static — it can change over time as the system learns and adapts in a knowledge discovery process. We model this using a time series of pairs (yi, xi), where yi is the i-th disturbance and xi is the i-th response. We then model the dynamics over time using a time series of events (selections and realized outcomes) {e}= {e1 , . . . , ej}, where ei is the i-th event of the disturbance-response (yi, xi) pair.

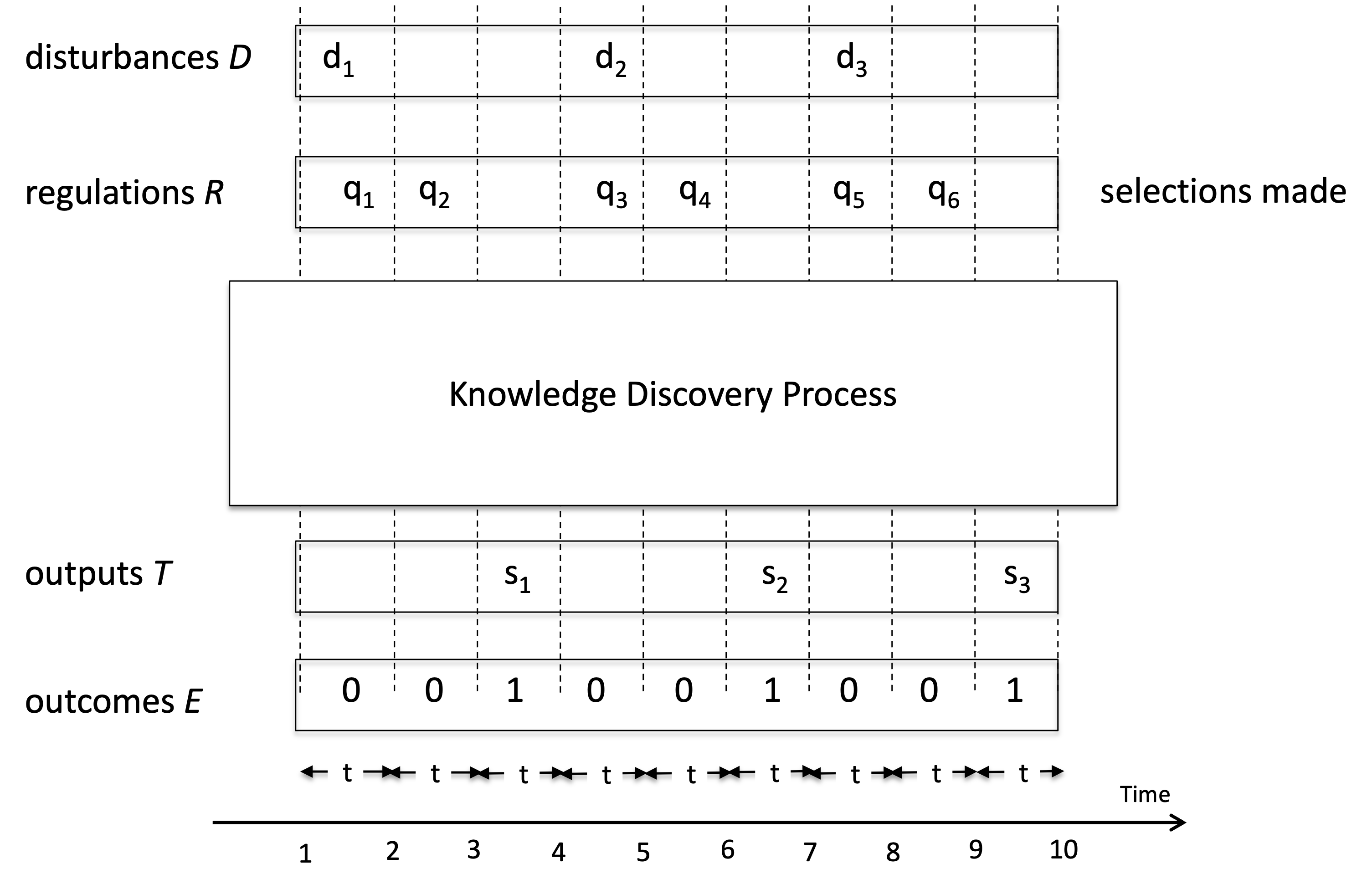

We illustrate the knowledge discovery process in Fig. 1.

Fig.1 A Knowledge Discovery Process. A regulator faces a sequence of disturbances Y and selects responses X over discrete time intervals t. The total available time T is divided into n unit intervals, each of which is used either to perform one optimal binary selection (one internal node traversal in a decision tree) or to emit one realized outcome in O. Three realized outcomes o1, o2, and o3 are produced. For disturbance y1, the response is already determined by the stored structural coupling between X and Y (i.e., ), so outcome o1 is emitted with zero selections. For disturbance y2, the regulator must search within the candidate response set , traversing four binary decision nodes (z1z2z3z4) before identifying the response and emitting o2. For disturbance y3, the candidate set requires two binary selections (z5z6) before outcome o3 is produced. Accordingly, the per-disturbance decision depths are: , , and . The expected number of selections per outcome is therefore E(k) = 2, which operationally estimates the latent conditional entropy H(X|Y) up to the standard +1 Shannon bound. This expected decision depth quantifies the Knowledge To Be Discovered required to produce an outcome.

We now generalize the Knowledge Discovery Process illustrated in Fig. 1. Consider a regulator that interacts with an environment in episodes. In each episode: A disturbance is observed at episode start and is treated as fixed for the episode. The regulator ultimately emits an episode-closing commitment oi (an externally visible acceptable outcome) by selecting responses. Let denote the available response set (Ashby’s ; the action alphabet). Let denote the regulator’s selected response random variable, with values in , distributed according to the regulator-induced policy (induced by its current coupling/structure ).

Within-episode selection model. The regulator is a black box. We do not observe its staged selection process. We assume only the following conditions:

- There is a single shared execution channel with no idle time, divided into atomic time units.

-

Each atomic time unit is used either to:

- perform one binary selection step, meaning the regulator receives (or generates) a binary discriminating signal whose realized value provides ≤ 1 bit of discriminating information relevant to determining which will be emitted for the given disturbance y for the current episode, or

- emit one episode-closing commitment (an externally visible acceptable outcome). Outcome emission is atomic and contains no hidden selection.

- Episode closure occurs only once the regulator has fixed the episode’s selected response (i.e., the closing commitment corresponds 1-to-1 with a finalized response choice, even if we do not inspect its content).

Information-theoretic bound

For each if the regulator’s within-episode binary selection strategy is optimal (minimizes for the given posterior ), then the expected number of binary selections required to identify X satisfies the Shannon bound:

(1)

Now introduce the latent (information-theoretic) quantity of the Knowledge Discovery Process: for each disturbance realization , the regulator faces a finite candidate set of admissible responses . We assume optimal binary selection: the multi-stage selection process Z1...Zk is implemented by the regulator through an optimal sequence of binary selections for identifying the response given .

The expected number of selections per episode is: . Although k is inferred as a concrete count per episode, it varies with which response X is correct; hence the latent expected count for that disturbance class is taken over the randomness of the under the fixed questioning strategy.

Crucially, is a model quantity, while is an externally measurable execution count.

Compatibility note (multiple acceptable responses). Even if multiple responses could lead to acceptable outcomes for a given y, this theory keeps X as the specific response selected/emitted by the regulator. Thus H(X∣Y) measures uncertainty about which response will be emitted under P(X∣Y), not uncertainty about success. Learning may structuralize tie-breaking so H(X∣Y)→0 for a stable task class.

Operational window accounting (black-box observable proxy)

Let denote the complete time-ordered sequence of events over a fixed window of n discrete time units, where each unit is fully utilized by exactly one atomic action on a single shared execution channel. Each interval is classified by the binary event-type indicator Bt which is 1 if the interval contains an episode-closing commitment and 0 otherwise.

The total number of counted episode closures in the window is

Thus the operational model estimates regulator-induced uncertainty through the average selection depth per counted closure, not by directly observing , , or the full Ashby outcome table.

In this base section, marks a closure that the ledger presently counts as an acceptable episode closure. Later, when rework is introduced, the accounting can be refined into gross closures, wasted closures, and net closures, without changing the basic meaning of as an event-type marker.

Partition the event stream into the S consecutive non-overlapping episodes , where episode wi corresponds to responding to one disturbance realization , consists of exactly one outcome that closes the episode and contains exactly ki selections preceding that outcome, By construction, the inferred total number of selections for the window satisfy . The window begins immediately after an episode-closing outcome and ends on an episode-closing outcome.

If the minimum outcome duration is one unit of time, equal to the time it takes to make one selection, then each action occupies one unit of time t. Hence the sum of S and Q equals the length of the time series. The total available time T is therefore: . We define as the execution rate of the channel, and since then . We now drop usage of n and instead use N as maximum action capacity (selections + outcomes) per window.

Consequently, over any observation window with maximum action capacity and observed number of outcomes , the inferred number of selections is:

(2)

Observable rework

Under fixed execution capacity, observable rework reduces net throughput because some channel capacity is spent on corrective or undo/repair commitments rather than on net new episode closures. This section is purely operational: it concerns externally visible execution counts, not the internal decomposition of the mapping update.

Accordingly, we distinguish:

- Observable rework: externally visible corrective, undo, rollback, replacement, or repair outcomes.

- Net negative learning: a worsening of the stored mapping in the coupling ledger, i.e. ΔtI < 0.

These are related but not identical. Observable rework may accompany net positive learning, zero net learning, or net negative learning. Therefore the counting model below should be interpreted as an execution-capacity accounting model, not as a direct observation of the internal knowledge ledger.

Per window t, let:

- Nt be anchored action capacity in the window (selections + outcome-emissions).

- Sgross,t be the number of gross outcome-emissions (all episode-closing commitments observed in the window).

- Wt be the number of those outcome-emissions that are observable rework outcomes, i.e. commitments whose purpose is to undo, repair, replace, or correct prior commitments, counted in the same window they occur and never retroactively, with 0 ≤ Wt ≤ Sgross,t.

- Snet,t be the number of net realized outcomes: .

- Qt be the number of binary selections (non-outcome action units): .

Here Wt is an observable artifact-level count. It is not equal to the negative part of the internal coupling change Lt = max(-ΔtI, 0). A nonzero Wt is evidence that corrective activity occurred, but it does not by itself imply ΔtI < 0.

Including W yields an operational equivocation rate per net outcome under non-retroactive windowing; it is not claiming that undo/repair commits are literally binary questions about X, only that they consume the same constrained channel capacity.

Selection-equivalent debit under fixed capacity

Because observable rework outcomes consume the same constrained channel capacity while not contributing to net new closures, we treat them operationally as a selection-equivalent debit. This does not mean that rework outcomes are literally binary questions about X; it means only that they occupy atomic action units on the same bounded execution channel.

Since wasted outcomes consume the same constrained channel capacity while not increasing , define the effective non-net-progress selection-equivalent effective debit:

Using and , we obtain:

Thus observable rework reduces net closures and correspondingly increases the effective debit counted against net progress.

Define the observed selection-equivalent depth per realized outcome:

(3)

Weak result: operational upper bound. Under the assumptions that (i) each non-outcome atomic unit contributes at most 1 bit of discriminating information relevant to fixing the selected response for the current disturbance, (ii) outcome emission contains no hidden selection, and (iii) episode closure occurs only after the response is fixed, the latent conditional uncertainty satisfies . Therefore any large-window empirical estimator of , such as Ĥ(X|Y) is an operational conservative proxy for the latent knowledge-to-be-discovered, subject to sampling and nonstationarity error.

Strong result: one-bit tightness under optimal binary selection. If, in addition, the within-episode discrimination strategy is optimal among binary decision procedures for identifying the selected response, then the standard question-depth bound in (1) applies. Hence, when the observation window is sufficiently large and stable so that the empirical mean depth approximates , the operational proxy will typically lie within about one bit of the latent conditional entropy H(X|Y).

is an operationally observable proxy for the (latent) expected within-episode decision depth . Under large windows / stability assumptions (so empirical averages represent expectations), . Empirically, approximates E[k] with sampling error that shrinks with window size N increasing. Combined with the information-theoretic bound above, this links the abstract “knowledge to be discovered” to externally observable execution counts through an expected-depth proxy.

In the idealized regime where the regulator’s within-episode questioning strategy is optimal, the window is large and stable so Ĥ(X|Y) ≈ E[k], the posteriors are close to uniform/power-of-two (balanced trees), then Ĥ(X|Y) will typically sit within about one bit of the true equivocation because E[k] does:

(4)

Knowledge To Be Discovered Conservative Estimator

Operationally, over a window with maximum atomic capacity N, gross outcome emissions Sgross, and wasted outcome emissions W, define::

(5)

This is the observed selection-equivalent decision depth per net realized outcome under non-retroactive windowing. It is not itself the true entropy H(X|Y), but a black-box observable quantity that increases whenever net stage closures are crowded out under fixed capacity. The atomic time unit for the rates is chosen fine-grained enough that each unit reveals ≤ 1 bit of discriminating information (i.e., any higher-bit test is decomposed into multiple counted units).

Ĥ(X|Y) measures the empirically observed expected decision depth per outcome. It is therefore an operational conservative proxy for the latent Knowledge To Be Discovered H(X|Y) under the counting model above. This upper-bound interpretation requires only that each counted non-outcome unit contribute at most one discriminating bit and that closure occur only after response fixation. A stronger near-tightness claim—namely that the proxy lies within about one bit of H(X|Y)—requires the additional assumption of optimal binary within-episode selection and representative large-window averaging. Whatever the true H(X|Y) is, it cannot exceed what is implied by the observed execution capacity.

Ĥ(X|Y) is an operational, black-box measure of the “knowledge to be discovered”: the observed selection-equivalent depth per net realized outcome. Rework increases Ĥ(X|Y) mechanically by reducing Snet under fixed N, capturing the crowd-out effect of wasted commitments on net episode closures.

The result is operational: it links an abstract information-theoretic quantity to directly observable execution counts , without assuming access to the true distribution. It provides an operational upper bound on conditional entropy under idealized assumptions (optimal binary selection, single shared channel, no idle capacity). It does not claim to recover the true entropy exactly in arbitrary systems.

We can rearange the bounds to be:

If there is no knowledge to be discovered, i.e. there is no need to make selections at all, then S equals N and H(X|Y) is zero. This is not redefining entropy — it is measuring it operationally.

Extra operational burden attributable to observable rework

For decomposition purposes, define the corresponding no-observable-rework baseline while holding Sgross,t fixed:

This is a conditional comparison only: it asks how much the operational proxy increases when some of the gross observed closures are reclassified as observable rework outcomes, while total gross outcome-emissions are held fixed. It is not a universal causal counterfactual about what would have happened in a different world.

The extra operational burden attributable to observable rework under that fixed-gross comparison is:

Therefore the operational burden induced by observable rework is strictly increasing in Wt and grows convexly as Wt → Sgross,t.

The role of Wt in this model is purely operational. Observable rework consumes capacity that could otherwise have produced net new closures, thereby increasing the observed selection-equivalent depth per net outcome. This is a throughput and capacity-crowding effect.

It should not be read as an identity between:

- artifact-level observable rework Wt, and

- internal net coupling loss Lt.

A window with Wt > 0 may still exhibit net positive learning in the internal ledger, and a window with ΔtI < 0 need not expose all of that loss through visible repair outcomes in the same window.

In summary, observable rework affects the operational proxy implicitly through bounded capacity and reduced net closures; it does not by itself identify the sign of the internal knowledge update.

6. Knowledge-Discovery Efficiency (KEDE) Metric

Now we generalize the Knowledge-Discovery Efficiency (KEDE) - scalar metric that quantifies how efficiently a system closes the gap between the variety demanded by its environment and the variety embodied in its prior knowledge[28].

We rearrange the formula (5) and insted of we use for notation simplicity. and get the formula for Knowledge-Discovery Efficiency (KEDE) metric[28]:

(6)

KEDE is a scalar metric that quantifies how efficiently a system closes the gap between the variety demanded by its environment and the variety embodied in its prior knowledge[28]. KEDE is an acronym for KnowledgE Discovery Efficiency. It is pronounced [ki:d].

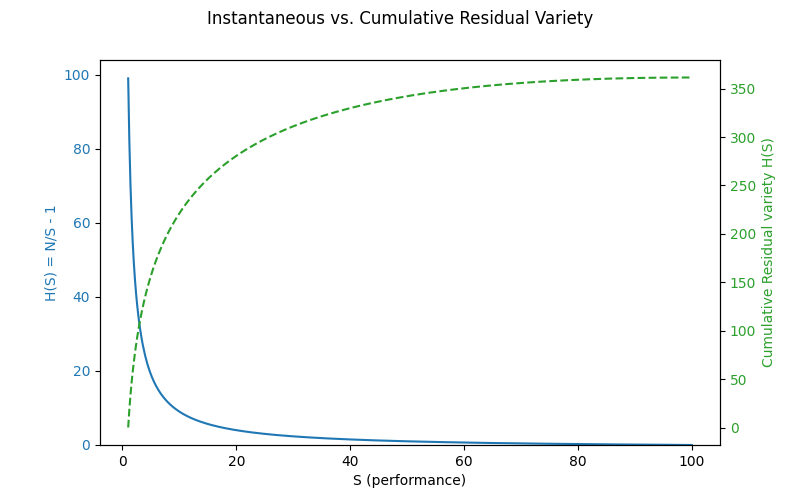

Efficiency means the smaller the average number of selections made per outcome the better. In other words - the less knowledge to be discovered per outcome the more efficient the knowledge discovery process is.

KEDE has the properties:

- It is a function of the missing information H

- Its maximum value corresponds to H equals zero i.e. there is no need to make selections, all knowledge is already discovered.

- Its minimum value corresponds to H equals Infinity i.e. we have no knowledge to start with.

- It is continuous in the closed interval of [0,1]. This makes it very useful to be used as a percentage. This is because we need to be able to rank knowledge discovery processes by efficiency. The best ranked knowledge discovery process will have 100% and the worst 0%. That is practical and people are used to having such a scale.

What does KEDE measure?

- Regulation consumes execution capacity to cope with missing knowledge.

- Knowledge discovery converts that consumed capacity into persistent internal variety, reducing future consumtion of the execution capacity.

- KEDE measures the efficiency of this conversion: how much execution capacity is spent on discovery versus production, under a successful-adaptation regime.

KEDE effectively converts the knowledge to be discovered H(X|Y), which can range from 0 to infinity, into a bounded scale between 0 and 1.

Due to its general definition KEDE can be used for comparisons between organizations in different contexts. For instance to compare hospitals with software development companies! That is possible as long as KEDE calculation is defined properly for each context. In what follows we will define KEDE calculation for the case of knowledge workers who produce textual content in general and computer source code in particular.

Anchoring KEDE to Natural Constraints

In our model, N is always the theoretical maximum action rate (selections + outcomes) in an unconstrained environment, and S is the observed outcome rate under specific conditions over a given interval.

A key question is how to assign a natural constraint to N. That is, what constitutes an appropriate reference value for the maximum action rate (selections + outcomes)?

We may turn to physics for an instructive analogy. A quantum (plural: quanta) represents the smallest discrete unit of a physical phenomenon. For instance, a quantum of light is a photon, and a quantum of electricity is an electron. In this context, the speed of light in a vacuum serves as a fundamental upper bound for N. However, identifying an analogous natural constraint for human activity—particularly knowledge work—presents greater challenges.

Consider the example of typing. Here, the quantum can reasonably be defined as a symbol, since it is the smallest discrete unit of text. A symbol may be a letter, number, punctuation mark, or whitespace character. To determine the appropriate bin width Δt, we refer to empirical data on the minimum time required to produce a single symbol. Typing speed has been subject to considerable research. One of the metrics used for analyzing typing speed is inter-key interval (IKI), which is the difference in timestamps between two keypress events. We see that IKI is defined equal to the symbol duration time t. Hence we can use the research of IKI to find the symbol duration time t. Studies have reported an average IKI of 0.238 seconds [26], yielding a maximum human typing rate of approximately N=1/t=1/0,238=4.2 symbols per second

A similar approach can be applied to tasks such as furniture assembly. In this case, a plausible quantum is a single screw tightened, since it represents a minimal, repeatable unit of outcome. We then identify Δt as the average time required to tighten one screw. Empirical studies report that this task typically takes between 5 and 10 seconds[34]. Using the upper bound, we estimate the maximum screw-tightening rate as N=1/t=1/10=0.1 screws per second.

This methodology offers a principled way to estimate N using domain-specific quanta and empirically grounded time durations, enabling the application of our model to a broad range of human tasks.

The next question concerns the appropriate definition of outcome for measuring S and N.

Both N and S can always be discretized—or “binned”—in a way that preserves the total information rate, regardless of whether the outcome arises from natural processes, human behavior, or machines. By choosing a bin width Δt small enough (e.g., milliseconds), the range of possible tangible outcomes within each bin shrinks dramatically. This reduced range leads to less uncertainty in each bin, which compensates for the smaller time interval. Yet the ratio

remains an accurate measure of information rate.

As Δt becomes smaller, the measurements of S and N become more precise, as they reflect outcome over finer time intervals. But how small should Δt be? This dilemma is resolved by considering the granularity of outcomes associated with the outcome. The set E of outcomes can be thought of as the effects of the regulation process — the resulting states after the regulator responds to disturbances. In our model E is a sequence of {0,1}, where 0 = wrong outcome(failure to regulate) and 1 = acceptable outcome. So the presence of a concrete outcome leads to a natural binning of the outcomes, It also enables a clear distinction between signal (the entropy associated with producing the outcome) and noise (the residual variability unrelated to success or failure).

For example, two distinct symbols typed (e.g., ‘a' vs. ‘b') are clearly different outcomes. However, if one symbol is typed in 91 milliseconds and another in 92 milliseconds, this minute variation is inconsequential to the outcome. Such timing fluctuations are typically unintentional, irrelevant to task performance, and should not be considered part of the outcome. In practical terms, if the theoretical upper bound N is known—for instance, 4.2 symbols per second as derived from human typing speed, and the observed rate is S=1 symbol per second, then time should be partitioned into one-second bins. Each bin then yields a single outcome: either 1 (a symbol was successfully typed) or 0 (no symbol typed or incorrect input).

This binning principle generalizes beyond typing. Whether analyzing foot strikes in trail running (where negligible spatial change occurs over milliseconds) or the discrete moves in solving a Rubik's cube (where each turn resolves multiple potential states into a single action), binning ensures that no intermediate state need be modeled explicitly.

7. Applications

The knowledge-centric perspective builds on Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety by emphasizing that successful outcomes depend not only on a system's range of possible responses, but also on its ability to select the right response for each disturbance. This requires internal “system knowledge” that maps disturbances to appropriate actions. As Francis Heylighen proposed in his “Law of Requisite Knowledge,” effective regulation demands more than variety—it demands informed selection[29]. This knowledge-centric lens provides a foundation for analyzing how systems—biological, technical, or organizational—achieve control not just through options, but through understanding. The model we present operationalizes this perspective by estimating the informational requirements a system must satisfy to achieve its observed level of regulatory performance.

In what follows, we apply this knowledge-centric perspective to a range of domains, including motor tasks and manual assembly, industrial assembly lines, software development processes, speed of light in a medium, intelligence testing and sports performance. In each case, the model enables us to estimate, in bits of information, the amount of knowledge a system must lack to produce its observed level of performance. By quantifying the knowledge to be discovered H(X|Y), we assess how much uncertainty was there in the system's ability to select appropriate responses. This allows us to compare systems not by tangible outcomes, but by the hidden knowledge structures required to achieve them, offering a unified lens for analyzing adaptation, skill, and control across diverse contexts.

Tightening screws

We can apply our model to motor tasks such as furniture assembly. In this context, a natural unit of outcome — or “quantum” — is the tightening of a single screw.

Skilled workers engaged in manual assembly tasks can typically insert and tighten standard screws at a rate of 6'-12 screws per minute under optimal, repetitive conditions — such as those found in furniture construction or industrial assembly lines. In contrast, automated screw-tightening machines can achieve significantly higher rates, often between 30 and 60 screws per minute [34] More complex manual tasks, such as high-torque applications involving ratchets or Allen keys, typically reduce the rate to 2'-4 screws per minute due to the increased effort and precision required. In surgical or medical contexts, such as orthopedic screw insertion, accuracy and the avoidance of overtightening are paramount; here, rates often fall to 1'-2 screws per minute, or approximately one screw every 30'-60 seconds [46].

| Context | Typical Rate (screws/minute) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Automated (machine) | 30'-60 | For comparison, not manual |

| Fast, repetitive tasks | 6'-12 | Assembly line, minimal torque required |

| High-torque/manual | 2'-4 | Metalwork, ratchets, Allen keys |

| Surgical/precision | 1'-2 | Orthopedic, high accuracy, low speed |

The key observation is that rates decrease as torque, task complexity, or required precision increases. If we take the machine rate as the maximum possible outcome N and the observed human rate as S, we can estimate the average number of bits of information H(X|Y) that the human operator must process per action.

This implies that the human must absorb approximately 4 bits of information, on average, to tighten a single screw under typical conditions.

The rate at which a person tightens screws depends on various factors, including:

- Screw type and size

- Material being fastened

- Required torque

- Tool used (screwdriver, ratchet, etc.)

- Operator skill and fatigue

This interpretation aligns with existing research, which suggests that task difficulty directly influences the amount of information a task imparts [47, 48]. When difficulty is appropriately matched to the individual's skill level, the task yields maximal informational value [49], and the time required reflects the interaction between task complexity and the individual's regulatory capacity [50].

Using our model, we transform a sequence of real-world actions in furniture assembly into a granular, time-based measure of regulatory capacity. This enables us to quantify — in bits — how much variety the individual must absorb in order to successfully complete the task.

Typing the longest English word

Let's use an example scenario to see Ashby's law applied to human cognition and knowledge work.

For that we'll have myself executing the task of typing on a keyboard the word “Honorificabilitudinitatibus”. It means “the state of being able to achieve honours” and is mentioned by Costard in Act V, Scene I of William Shakespeare's “Love's Labour's Lost”. With its 27 letters “Honorificabilitudinitatibus” is the longest word in the English language featuring only alternating consonants and vowels.

The way I will execute this task is to go to the "play text" or "script" of “Love's Labour's Lost”, look up the word and type it down. The manual part of the task is to type 27 letters. The knowledge part of the task is to know which are those 27 letters.

In order to track the knowledge discovery process I will put "1" for each time interval when I have a letter typed and "0" for each time interval when I don't know what letter to type.

I start by taking a good look at the word “Honorificabilitudinitatibus” in the script of “Love's Labours' Lost”. That takes me two time intervals. Then I type the first letters “H”, “o”, and “n”.I continue typing letter after letter: “o”, “r”. At this point I cannot recall the next letter. What should I do? I am missing information so I go and open up the script of “Love's Labours Lost” and I look up the word again. Now I know what the next letter to type is but acquiring that information took me one time interval. This time I have remembered more letters so I am able to type “i”,”f”,”i”,”c”,”a”,”b”,”i”. Then again I cannot continue because I have forgotten what were the next letters of the word, so I have to look it up again.in the script. That takes two more time intervals. Now I can continue my typing of “l”,”i”,”t”. At this point I stop again because I am not sure what were the next letters to type, so I have to think about it. That takes one time interval. I continue my typing with “u”,”d”,”i”. Then I stop again because I have again forgotten what were the next letters to type, so I have to look it up again in the script of “Love's Labours Lost”. That takes two more time intervals. Now I know what the next letter to type is so I can continue typing “n”,”i”.At this point I cannot recall the next letter. so I have to look it up again in the script. That takes two more time intervals. After I know what the next letter to type is I can continue typing “t”,”a”,”t”,”i”,”b”,”u”,”s”. Eventually I am done!

At the end of the exercise I have the word “Honorificabilitudinitatibus” typed and along with it a sequence of zeros and ones.

|

|

|

H | o | n | o | r |

|

i | f | i | c | a | b | i |

|

|

l | i | t |

|

u | d | i |

|

|

n | i |

|

|

t | a | t | i | b | u | s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

In the table we have separated the manual work of typing from the knowledge work of thinking about what to type.

The first row of the table shows the knowledge I manually transformed into tangible outcome - in this case the longest English word. The second row of the table shows the way I discovered that knowledge. There is a "0" for each time interval when I was missing information about what to type next. There is "1" for each time interval when I had prior knowledge about what to type next. Each "0" represents a selection I needed to ask in order to acquire the missing information about what letter to type next. Each "1" represents prior knowledge.

In the exercise above we witnessed the discovery and transformation of invisible knowledge into visible tangible outcome.

KEDE calculation

We can calculate the KEDE for this sequence of outcomes.

We can also calculate the knowledge discovered H(X|Y) in bits of information.