Methods for Knowledge Discovery

Based on the Cynefin framework

Dynamics

This contains substantial material from Cynefin Training programmes and Dave Snowden's blog posts. The author acknowledges that use, and further that his use of that material are his own and should not be considered as being endorsed by theCynefinCompany or Dave Snowden.

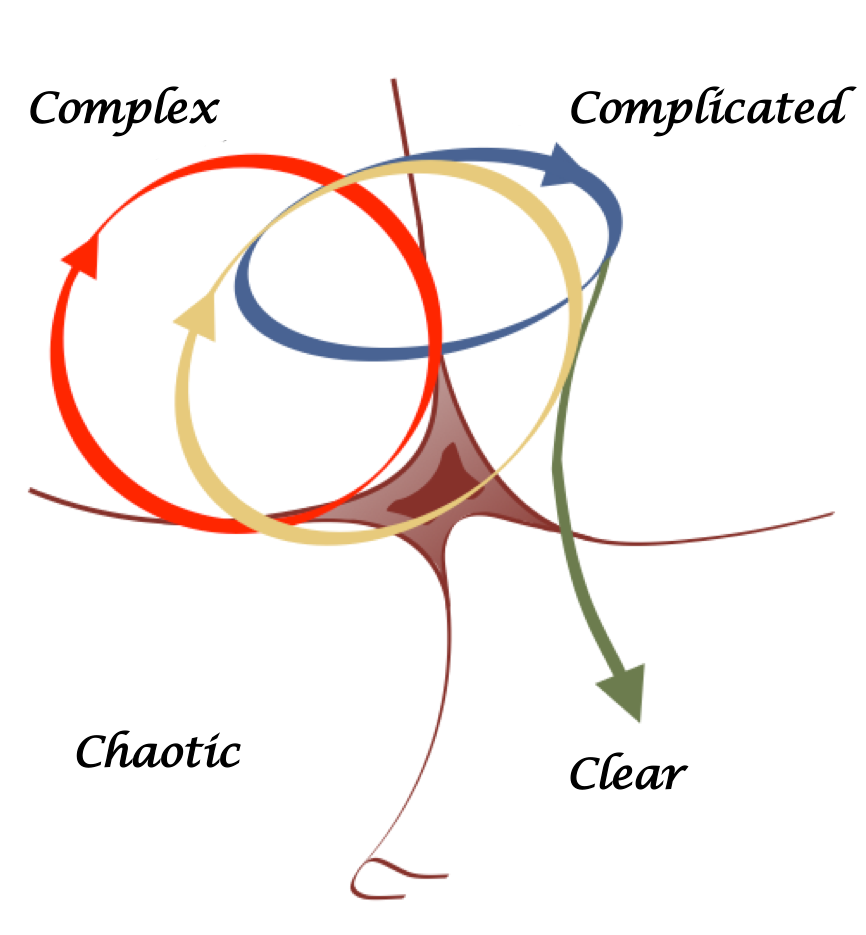

The Cynefin framework is first about contextual awareness, followed by contextually appropriate action. So the first thing is to understand what type of domain we are in. The second thing is what are the dynamics that shift between domains. Hence Cynefin has two classification systems: domains and dynamics. As we increase the level of uncertainty the dynamic classification becomes more important than the domain classification.

In an organization all of the dynamics and all of the domains will be in operation at the same time. For example, at the board level things may be stable while at the team level things may not be stable. Complexity is fractal. Dynamics and domains are value free! The value is the ability to move things between domains.

All four dynamics are presented on Figure 3. The stable dynamic is shown in blue: it moves between the complex and the complicated domains and if needed back again. The yellow line shows the dynamic of shallow dive into chaos: breaking up established practice to allow novel practice to emerge or reset the system to allow a new stable dynamic to emerge. The green line shows the dynamic of going down into the Clear domain: when we settle on one best practice of doing things and we enforce that in all bar exceptional circumstances. The red line shows the grazing dynamic in which the overall volatility is such that stability is rarely other than transitionary and we stay in complexity while constantly skim the surface of chaos[1].

Stable dynamic

The most stable dynamic is the movement between the Complex and the Complicated domains[1]. Some people think that complicated has a negative connotation. They cherish complexity! We argue that complicated is not negative. Something that can turn Complex into Complicated is great, because if it does it coherently it allows for scalability and repeatability. Pretending it's Complicated when actually it's Complex - that's wrong.

For complex problems we employ numerous coherent (to the individual and not the group as a whole, although the group must accept that it is a valid view point), safe-to-fail, fine-grained experiments in parallel which will provide feedback on what works and what doesn't. We manage the experiments as a portfolio. Some of the experiments must be oblique, some naïve, some contradictory, some high-risk/high-return types. When we run several probes in parallel, they will change the environment anyway so the logic is that all probes should be roughly of the same size and take roughly the same time. In practice those experiments generally merge, mutate or fail and a solution or solutions emerge. There is concern that there are insufficient coherent hypotheses, or more important insufficient contradiction. If that is the case then we should be concerned that we may have insufficient range of experiments and may be at risk of missing a key weak signal, or signals.

Then we apply sense-making to the feedback and respond by continuing or intensifying the things that work, correcting or changing those that don't. As they start to work in a consistent way we apply constraints.

If we continue with the probes it is under increased constraints. Now we get onto the key test - if we increase the constraints and it produces unexpected consequences, we relax the constraints and keep it into the complex. If when we increase the constraints it produces predictable behavior we've made it complicated and that's good news.

Any linear experimental testing/prototyping process is effectively a Complex to Complicated transition in its nature. If we were doing parallel, smaller experiments it would be staying in the Complex domain.

Now we've successfully moved into the Complicated domain. That Complex to Complicated cycle is essential. Complicated is for exploitation, Complex is for exploration.

The mistake people do is when they manage to shift it to Complicated they assume it will always work and they don't carry on testing it. But in reality the context may shift so the constraints put in place may no longer produce predictability even though they did before. If they stop producing predictability, then we cycle back into Complex. There is a natural cadence of that movement.

Going too slow or too fast between the domains is a mistake. Getting the cadence right is an experimental process. Getting the right cadence means stability.

Innovation

This dynamic is based on the shallow dive into chaos.

In general, people do the movement to complicated but they don't do the reverse. If we don't do the reverse what actually will happen is that every now and then we'll have to do “shallow dive into chaos”.

Basically we have allowed things to become entrained, so we;ve got governing constraints when we should have gotten back to Complex. We have to break things up to allow them to reform. We have to get a bit chaotic. And we have to be careful with it.

In the Chaotic domain the novelty arises from stress, from a complete break with the familiar[2].

Hans Selye is frequently claimed to be the father of the stress concept. Since he used the term stress on the response rather than on the stimuli, he had to invent a word for the stimulus that triggered this response. This is the origin of the term “stressor”.

Given that a particular stressor, or set of stressors, is perceived as threatening or negative, humans report this as “stress”. The stress is a general, unspecific alarm response occurring whenever there is something missing i.e. there is a discrepancy between goals and reality In general, the alarm occurs in all situations where expectancies are not met. The alarm continues until the discrepancy is eliminated, by changing the expectations, or the reality, when this is possible. The alarm is uncomfortable, the alarm “drives” the individual to the proper solutions. Stress is an adaptive response [3].

When under stress, people face a coping decision. They could either accept or not accept the opportunity to cope with the stress. As a term coping covers either the act or the result. We'll look into both starting with coping as the result i.e. reduced level of stress. When coping means the result then it could be coping, helplessness or hopelessness [3].

We have coping when the individual establishes an expectancy of being able to cope i.e. an expectancy that most or all responses to a stressor lead to a reduced stress level. To emphasize - it is not the action, or the feedback from evaluation of the action, that matter, but the subjective feeling of being able to cope that reduces the stress.

When coping is not possible we have two cases - helplessness and hopelessness. Helplessness is the acquired expectancy that there is no relationship between anything the individual can do and the level of stress. The individual has no control. However, when the individual “accepts” that there is no solution, the level of stress may be reduced. It may also be reduced if the helplessness leads to secondary gain and support from society. In such cases, helplessness may function as a coping strategy, and the secondary gain may reinforce and sustain the helplessness condition. Hopelessness is the acquired expectancy that most or all responses lead to a negative result. There is control, responses have effects, but they are all negative. The negative outcome is personal fault since the individual has control. This introduces the element of guilt.

The second meaning of coping is the coping act - to reduce or eliminate the stress itself by action. When the stressor is a resource constraint the literature proposes two identifiable coping strategies that humans, who believe are able to cope with the stressor, are likely to pursue - a simplification-focus strategy and a compensation strategy.

Simplification-focus coping strategy occurs when humans eliminate unnecessary or less valuable parts of the work process. It can be perceived as analogous to revamping a value-chain, re-engineering a business process or waste elimination in Lean. Simplification is not always a part of the strategy, as people sometimes proceed directly to the focusing action: concentrating on the key components of the work process.

A compensation coping strategy involves closing the gap caused by the resource constraint by utilizing coping assets that compensate for the constrained resources. We define coping assets as the skills and capabilities that the organization possesses or can gain access to and can utilize when dealing with resource constraints [4]. Unlike the simplification-focus strategy, where people eliminate parts of the work process and focus on the remaining ones, in compensation they add to it by utilising their coping assets. People exploit compensation because the challenge pushes them to optimally utilize the materials, knowledge, people and other processes that are already available [5]. Another form of compensation strategy is bricolage. Bricolage refers to solving problems and taking advantage of opportunities by combining existing resources [6]. A great example of this strategy is Kaizen in Lean [7].

A simplification-focus strategy is exploitative in nature. It entails the exclusion of processes or materials and thus focuses only on components that are already part of the work process. As such, this strategy limits the ability to achieve benefits that only exist outside the boundaries of the system.

A compensation strategy is exploratory in nature. Compared to a simplification-focus strategy, a compensation strategy requires people to add to the existing process and knowledge by borrowing knowledge and resources from outside the closed system, outside the scope of the current work process, even outside the organization. Thus, its impact may extend beyond the boundaries of the stress i.e. it actually over-compensates because entails new and meaningful learning opportunities.

Our distinction between the two coping strategies and their associations with exploitative and explorative learning processes is particularly valuable in the context of innovation. The strong link between simplification-focus and exploitative learning indicates that a simplification-focus strategy is likely to lead to incremental innovation. Conversely, the strong link between a compensation strategy and explorative learning indicates that a compensation strategy is likely to lead to radical innovation. Importantly, both coping strategies yield positive innovation performance; the type of innovation, however, is a key dimension that may distinguish between the two strategies.

In summary, a compensation strategy provides a richer toolbox for current and future encounters with challenges, and therefore it is superior to a simplification-focus strategy [4]. Still, a single organization may implement both coping strategies in a case in which managers eliminate non-valuable work process actions through simplification-focus and add valuable actions through compensation. Therefore, despite opposing behaviors, it is possible that the implementation of these two approaches overlaps as manifested in Lean.

An example of how novelty arises from stress as described above is the way Honda developed new products as described by an executive “It's like putting the team members on the second floor, removing the ladder, and telling them to jump or else. I believe creativity is born by pushing people against the wall and pressuring them almost to the extreme.”[8] This comes form the article which is claimed to be origin of Scrum :“Scrum for software was directly modeled after "The New New Product Development Game"; by Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka published in the Harvard Business Review in 1986. ” [9]

Another example comes form from Ohno: “I strongly believe that necessity is the mother of invention… The key to progress in production improvement, I feel, is letting the plant people feel the need” [10].

Let's take stock and list the necessary but not sufficient conditions for innovation:

- Stress caused by a stressor, or set of stressors e.g. resource constraints;

- Subjective feeling of being able to cope;

- Perspective shift by borrowing knowledge and resources from outside the closed system, outside the scope of the current work process, even outside the organization itself;

Stress, coping, perspective shift. Remember cognitive activation? It's only when the old patterns will no longer survive then we see things differently. So if we starve people of resource, we help them cope and we put them close to different sources of knowledge then people will be wonderfully inventive.

Down into Clear

Some things go down into the Clear domain. In terms of innovation things go there to die. This isn't a value statement. Clear may contain 90% of the value of an organization. The point is we only put things into Clear when we don't need to change them. If we need to change them Clear is a bad place to go [1].

With human systems if we impose excessive constraints sooner or later people will find ways to work around it. Sometimes the only way to get the job done is to break the rules. That actually is a habitual pattern, an attractor for breaking the law. The energy consumption of the system goes up - it may appear to be efficient on the surface but the reality is it's extremely inefficient.

If rules breaking is an exception than it works differently. If we follow a Complexity Thinking based approach we would have a few more rigidly enforced rules, and then rules about who and when can break the rules. We also have heuristics which operate on the other side of the rule boundary.

Grazing dynamic

It is all too common when faced with complexity people don't absorb it but try to eliminate it. The fluidity of complexity is far too scary. Increasingly these days we find that the level of volatility is such that things never stabilize long enough in any type of regularity and we never really get certainty. If that's the case we need to stay in the Complex domain while constantly skim the surface of chaos. That is called Grazing dynamic[1].

Different types of problems require different management approaches. For Complex problems the role of management is to create and relax constraints as needed and then dynamically allocate resources where patterns of success emerge. We manage what we could manage - the boundary conditions, the safe-to-fail experiments, rapid amplification and dampening. By applying this approach, we discover value at points along the way.

The way of learning and adapting to a complex environment is by running safe-to-fail experiments i.e. catalytic probes. Does a “probe” means the scientific type of experiment? Absolutely no! They are not experiments in the strict 19th century scientific context. A probe is an experiment in the more general sense of the word - do something and see if it works. Experiment means risk reduction, betting after the horse race has started. With probes we use the present in order to affect the horse race while it's still on.

Here is how we do a probe. We identify any coherent hypothesis about what potentially could improve things. To agree that our hypothesis is coherent is not the same as to agree that we are right. Every probe gets a small amount of resources to run a short-cycle, safe-to-fail experiment. The rule is very simple - the experiment to be safe-to-fail. That means if it fails we'll be able to recover [11].

Each probe should be:

- coherent

- safe-to-fail

- finely grained, tangible

We run all probes in parallel because we want to stay in the complex domain. Actually this is a significant conflict resolution tool, because if we do only one probe in sequence somebody has to be right so everybody has to emphasise the evidence which supports their proposition to get resources. Hence they get more and more defensive about it and less and less prepared to think it's wrong and attack other people's ideas more. That's when the things are binary: in order to win we have to show that the other side is wrong. On the other hand, if we say: I don't agree with you but I think your idea is coherent, that's a very different proposition. We can reduce strategic conflict.

The heuristic on a portfolio of probes is - over the whole portfolio if some experiments succeed others must fail. Because if all of them can succeed we are not spreading our senses wide enough. We never learn by doing something right, because we already know how we do it. This way we only learn by making mistakes and correcting them.

The point is - if we don't know what's going to happen we need broad expansion. We have to run all of probes and not shut some of them down. That's because the one that works in the present circumstances this time may not work in other circumstances next time - because the experiments will change the space anyway! In a complex system every intervention changes the thing observed. It's not about if this hypothesis is right - if the hypothesis is coherent then next time it may work, because next time round the butterfly will flap its wings in a different sequence.

Overall the portfolio should contain:

The first portfolio rule is that at least one of the experiments should be oblique. Oblique means to try to resolve a related but a different problem. It basically says: when we are stuck trying to solve the problem, we forget about it and try to do something else we often find a solution for the initial problem.

The second rule is at least one of the experiments must use a naïve asset. That means getting somebody who never addressed the problem before but has deep expertise in a related field to try and come up with a solution. The creative insights come from people that aren't harnessed with the preconceptions and assumptions that characterise the field.

What we are doing here is managing the portfolio of experiments to force diversity. As experiments are run the space will change and sustainable solutions will become more self-evident. Experiments in this regards are generally fusions. When we run several probes in parallel, they will change the environment anyway so the logic is that all probes should be roughly of the same size and take roughly the same time.

This is a very time-consuming effort, and traditional management is likely to fall back into command and control mode, as this promises to ostensibly provide for quick and efficient answesr[12]

Scrum, at least its initial application, is a great example of how to stay in the complex domain while constantly skim the surface of chaos. As Jeff Sutherland said:“In Scrum, we introduce chaos into the development process and then use an empirical control harness to inspect and adapt a rapidly evolving system.”[13]

Scrum was formally presented by Scrum co-creators Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland in 1995 at the OOPSLA Conference in Austin, Texas. The presentation “SCRUM Development Process” they gave back than is still available. Here are some of the lines in it:

“The system development process is complicated and complex. Therefore maximum flexibility and appropriate control is required. Evolution favors those that operate with maximum exposure to environmental change and have optimised for flexible adaptation to change. Evolution deselects those who have insulated themselves from environmental change and have minimized chaos and complexity in their environment.”[14]

We acknowledge that the above sentences are made on purpose. Per Cynefin we know what chaos, complex and complicated means.

“The closer the development team operates to the edge of chaos, while still maintaining order, the more competitive and useful the resulting system will be.”[14]

“Operating at the edge of chaos requires management controls to avoid falling into chaos.”[14]

We don't have time to get into this, but every Scrum practitionar should be able to build map Scrum to what we said above.

What Scrum is supposed to do is to get a set of complex options, probe them in parallel and spill as a complicated solution whatever is ready to de delivered . This cycle is bounded in a sprint.

Works Cited

1. Snowden, D. (2015, July 2). Cynefin dynamics. Cognitive Edge. /blog/cynefin-dynamics/

2. Snowden, D. (2019, April 16). Cynefin St David's Day 2019 (2 of 5). Cognitive Edge. /blog/cynefin-st-davids-day-2019-2-of-5/

3. Ursin, H., & Eriksen, H. R. (2004). The cognitive activation theory of stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(5), 567–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00091-X

4. Rosenzweig, S., & Grinstein, A. (2016). How Resource Challenges Can Improve Firm Innovation Performance: Identifying Coping Strategies: Resource Challenges and Coping Strategies. Creativity and Innovation Management, 25(1), 110–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12122

5. Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). MAKING FAST STRATEGIC DECISIONS IN HIGH-VELOCITY ENVIRONMENTS. Academy of Management Journal, 32(3), 543–576. https://doi.org/10.2307/256434

6. Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329–366. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329

7. Sugimori, Y., Kusunoki, K., Cho, F., & Uchikawa, S. (1977). Toyota production system and Kanban system Materialization of just-in-time and respect-for-human system. International Journal of Production Research, 15(6), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207547708943149

8. Takeuchi, H., & Nonaka, I. (1986, January 1). The New New Product Development Game. Harvard Business Review, January 1986. https://hbr.org/1986/01/the-new-new-product-development-game

9. Sutherland, J. (2011, October 22). Takeuchi and Nonaka: The Roots of Scrum—Scrum Inc. https://www.scruminc.com/takeuchi-and-nonaka-roots-of-scrum/

10. Ohno, T. (1988). Workplace Management (First Edition edition). Productivity Pr.

11. Snowden, D. (2011). Safe-to-Fail Probes—Cognitive Edge. http://cognitive-edge.com/methods/safe-to-fail-probes/

12. Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. E. (2007, November 1). A Leader's Framework for Decision Making. Harvard Business Review, November 2007. https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making

13. Sutherland, J. (2008, August 10). Scrum Log Jeff Sutherland: 08/01/2008—09/01/2008. http://jeffsutherland.com/2008_08_01_archive.html

14. Schwaber, K. (1997). SCRUM Development Process. In J. Sutherland, C. Casanave, J. Miller, P. Patel, & G. Hollowell (Eds.), Business Object Design and Implementation (pp. 117–134). Springer London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-0947-1_11

Getting started